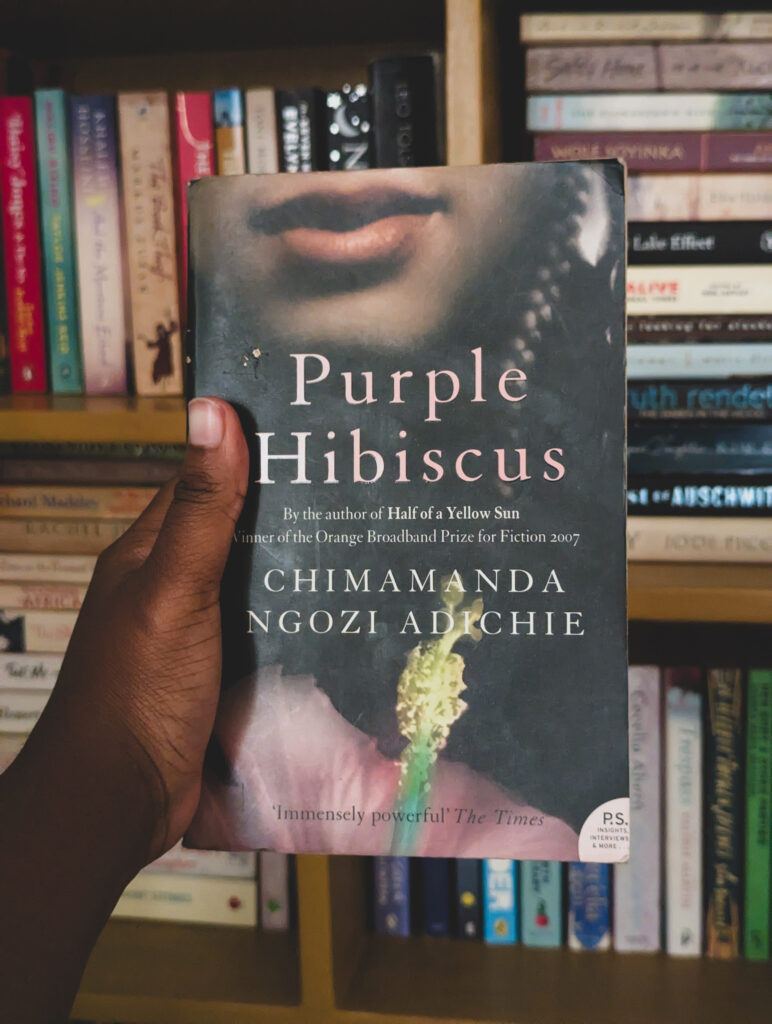

Fifteen-year-old Kambili and her older brother Jaja lead a privileged life in Enugu, Nigeria. They live in a beautiful house, with a caring family, and attend an exclusive missionary school. They’re completely shielded from the troubles of the world. Yet, as Kambili reveals in her tender-voiced account, things are less perfect than they appear. Although her Papa is generous and well respected, he is fanatically religious and tyrannical at home—a home that is silent and suffocating.

As the country begins to fall apart under a military coup, Kambili and Jaja are sent to their aunt, a university professor outside the city, where they discover a life beyond the confines of their father’s authority. Books cram the shelves, curry and nutmeg permeate the air, and their cousins’ laughter rings throughout the house. When they return home, tensions within the family escalate, and Kambili must find the strength to keep her loved ones together.

Purple Hibiscus is an exquisite novel about the emotional turmoil of adolescence, the powerful bonds of family, and the bright promise of freedom.

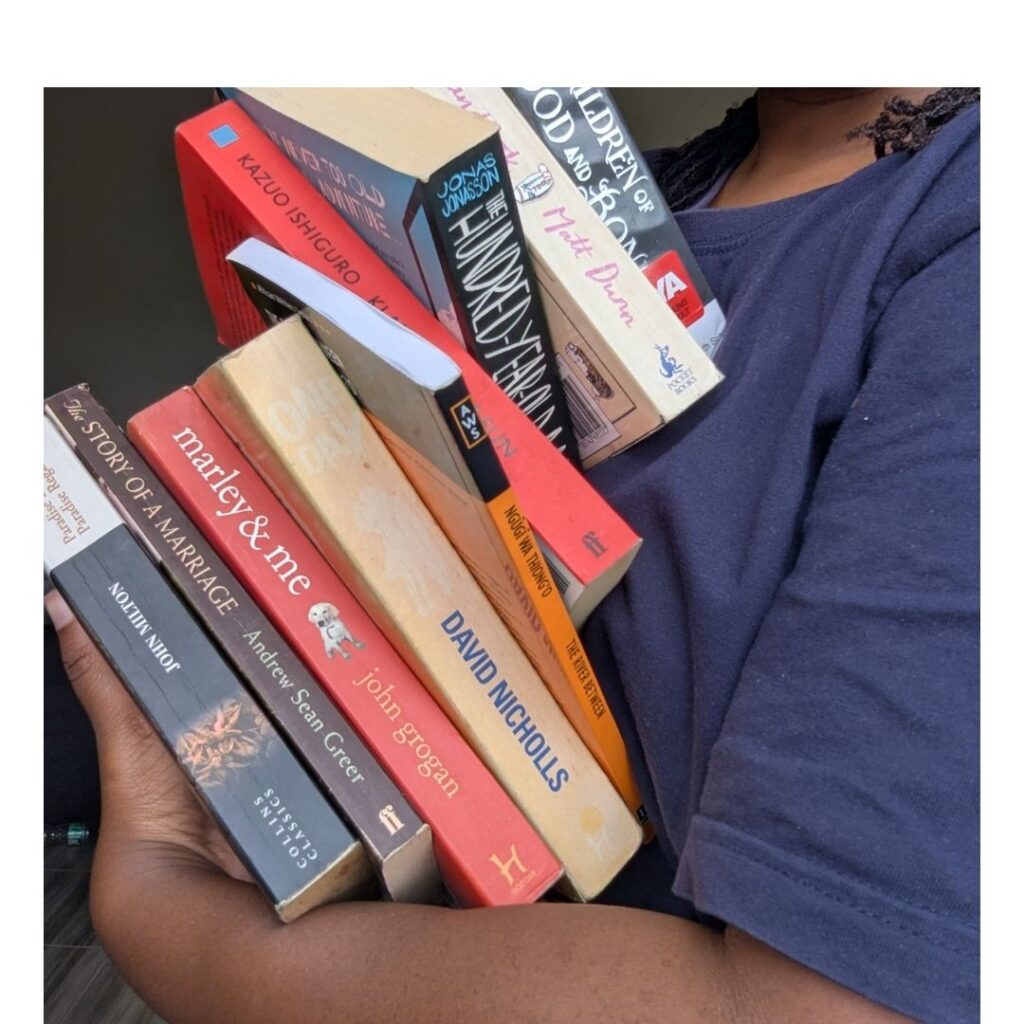

I’ve been putting off reading any of Chimamanda’s novels for a long-overdue minute. Not for any profound reason but because reading is hard, and if I’m going to do it, I’d rather it be with mental lollipops – the brain’s equivalent of artificial sweeteners and empty calories, packaged in goofy romances.

However, at the start of May, my sister posted Purple Hibiscus as her current read. I texted her and said I might as well do an accidental buddy read with her. This was actually my second attempt at reading the book, because I also had a physical copy. The first was in January, when I agreed to buddy read it with a friend (because it’s on my TBR this year), and then promptly abandoned her to read other books I was more interested in. Sorry, Glory.

[That] There were painfully scattered bits inside me that I could never put back because the places they fit into were gone.

― Chimamanda Ngozie, Purple Hibiscus

First things first, I cannot believe Chimamanda wrote this gem when she was my age of twenty-six. I can barely string together a coherent sentence, and she gave the world this.

To put it lighter than a feather, there’s no doubt she writes beautifully. Her descriptions are loud, the narration vivid, and the writing as a whole is incredibly rich. That being said I found a good chunk of this book flat. Engaging somewhat, but very, very flat.

The novel is a coming-of-age story (a phrase I borrowed from the many people who’ve reviewed this book before me. I hear it often but don’t really know what it fully entails until I asked my mad titan literary connoisseur best friend, Ngasa what it meant). It’s told through the eyes of Kambili, a 15-year-old girl who lives with her older brother Jaja and Mama, under the tyrannical rule of her wealthy, fanatically Catholic father.

Those few pages set the scene about exactly what their lives look like. Their father’s character is maniacal at worst and complex at best. He clearly loves his family and yet somehow remains the weapon formed against them. He’s an abusive disciplinarian who keeps everyone in line and justifies it all as “God’s plan.”

One scene that captures Papa’s character well is his evening tea ritual. He insists Kambili and Jaja sip it with him because “you share with the people you love.” But the tea is always scalding hot and burns their tongues. It’s a perfect metaphor to show that he’s both loving and violent.

A love sip, he called it, because you shared the little things you loved with the people you loved.

― Chimamanda Ngozie, Purple Hibiscus

Anyway, all this is set against the backdrop of Nigeria going through a whole political revolution, and I know there’s some parallels to draw, some things to unpack but I won’t even get into that.

What I will get into is that somehow, somewhere, Kambili and Jaja end up staying with their Aunty Ifeoma and her kids at the university where their aunt works in Nsukka. And there, they experience freedom so profound to their being that it radicalises them – especially Jaja. Aunty Ifeoma is the obvious foil to Papa. Where he’s rich, she’s not so much. Where he’s strict, she’s soft and fluid. She’s just great, honestly. And it shows in how her kids move through the world – especially compared to Kambili and Jaja. But at least it rubs off on them and it’s really lovely to see.

The beginning of this story is pretty decent but I found the middle to sort of fizzle and drag. Some beats feel almost repeated. I honest to God thought I’d give this book a three stars because of that. But the last few 100 or so pages of this story moved me in ways I did not expect to be moved. It was a rollercoaster. I was uncomfortable. I was sad. I was angry. And my reactions were so animated and vocal that Ngasa sent me this:

I hadn’t noticed but somewhere down the pages, a fondness grew. I felt a sort of second hand saudade – missing a place I’ve never been to when things started to fall apart ( a small nod there, if you know you know.). Towards the end there, there was a sort of mono no aware1 but only because I knew these characters loved where they were and would miss Nsukka when they had to leave. I think theses feelings are a testament to the calibre of Chimamanda’s writing.

There was a helplessness in his joy. The same kind of helplessness in that woman’s despair.

― Chimamanda Ngozie, Purple Hibiscus

By the end of reading this, my only hang up was that I thought Jaja and Kambili’s relationship wasn’t explored enough. Though spoken about quite a lot, I do not think Jaja was laid out. I find so much potential in his character but I feel we are given scraps. I would have argued that maybe it’s because we aren’t in his head, but I find other characters examined better as well, such as Aunty Ifeoma and Amaka and even a priest and I think it’s an injustice to Jaja because he is so pivotal and larger than life. Towards the end, there’s a line that says “there’s so much that is still silent between Jaja and me” and I think though not what it meant in the story, encompasses my sentiments.

My final thoughts on this are that, despite every thing going on, this reads like a love letter to youth but particularly youth in Nsukka – a place in Nigeria that I’ve never heard of until I read this book. Chimamanda grew up there and I can tell by the way she writes about it in Purple Hibiscus that she is fond of the place, regardless of the fact that she no longer lives there. In the story you get a clear sense that despite all the political mess happening around, this is a place that held (and maybe still holds) something good.

All in all, I think this is an amazing book. I wish I hadn’t put it off for so long. It’s a low 4 stars for me, but a 4 stars regardless.

He will never think that he did enough, and he will never understand that I do not think he should have done more.

― Chimamanda Ngozie, Purple Hibiscus

- Japanese term for the awareness of impermanence or transience of things, and both a transient gentle sadness or wistfulness at their passing ↩︎